THE DYTP MOURNSÌý³Ù³ó±ðÌýÌýof our colleague and friend,ÌýDavid Shneer. On two occasions David contributed to the DYTP and his entries are foundÌýÌý²¹²Ô»åÌý. Below, members of DYTP’s research team and advisory board reflect on their encounters with David and his work.

Joel Berkowitz

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, DYTP Co-Founder

I first met David at a Yiddish Studies conference in Krakow in 1999. I remember being struck right away by how his broad smile seemed to arrive several moments before the rest of him did, and by his lively engagement with ideas. A notable moment at that conference came in the form of an animated exchange between David and anÌýéminence griseÌýamong Soviet Jewish historians. While I didn’t know the subject matter well enough to evaluate it fully, it felt as if I was witnessing a snapshot of a paradigm shift in how Soviet Jewish culture was interpreted. And sure enough, David was in the process of becoming a leading voice among a new generation of scholars in that field, as other contributors to this post so vividly describe.

Fast forward a few years, and David and I would find ourselves in new jobs, directing and teaching in Jewish Studies programs. Though we lived and worked far from one another, we would cross paths in person on various occasions, leaving me with vivid memories of conversations over the years in conference-hotel hallways, during and between sessions at professional workshops, at annual breakfast meetings of the editorial board ofÌý, or over drinks at the bar at the end of long (but happy) days of delivering and listening to conference papers. Many of these were in the company of numerous mutual friends, like my fellow contributors here. All of them were enlivened by David’s relentless energy, inquisitiveness, warmth, and kindness.

Fast forward another decade or so, to 2013, when I finally found the perfect opportunity to bring David to my university in Milwaukee: to deliver aÌýÌýmarking the anniversary ofÌý, and give some other more intimate presentations as well. I’ve hosted many remarkable speakers over the years, but David’s visit still stands out: among other reasons, because of his boundless energy, the ease with which he interacted with people, and his versatility as a scholar. In the course of a thirty-six-hour visit, David gave three public talks and also visited a class I was teaching and co-taught a session with me on Soviet Yiddish theatre and film. The class visit provided the double delight of watching clips featuring the great Soviet Yiddish actorÌý, and having them put in context by one of the leading scholars of Soviet Jewish culture. My students participated with all the enthusiasm of Mikhoels’s characterÌýÌýdoing his part to help turn the city of Magnitogorsk into a manufacturing hub.

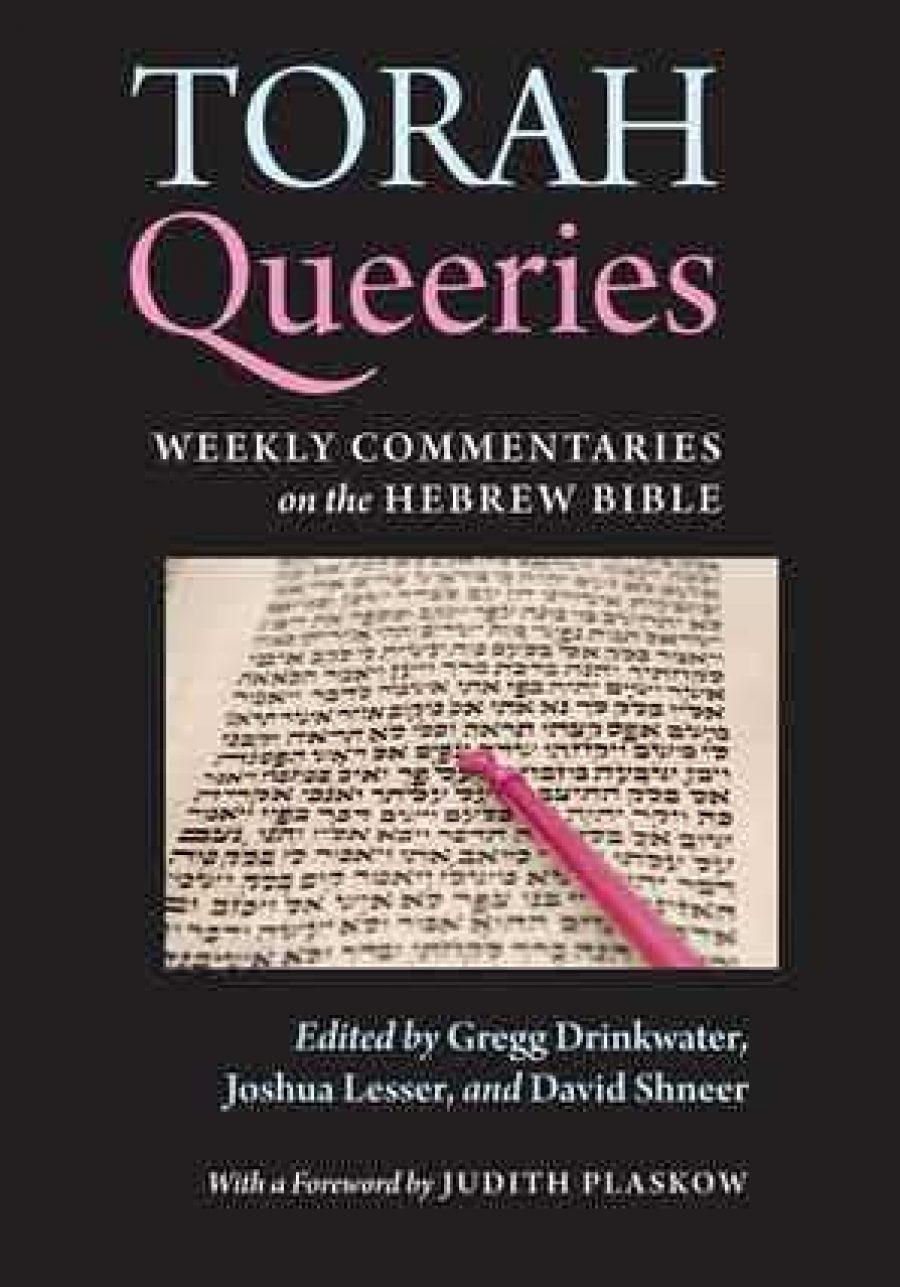

In addition to his well-received Kristallnacht lecture, from material in his bookÌý, David gaveÌýÌýin my campus’s Hillel building: a workshop related to his co-edited volumeÌý, on LGBT perspectives on the Torah, and personal reflections on his work as a Jewish LGBT activist. Stories David told in the latter session resonated particularly strongly with a community member from an older generation, who responded with stories of his own engagement with the Jewish LGBT world over an even longer period of time. It was one of those moments one always wishes for, when the visiting lecturer not only makes a mark on the audience, but is in turn enriched by that interaction.

The Digital Yiddish Theatre Project mourns David’s premature passing and cherishes his memory. We feel fortunate that his prolific writing on Jewish cultural history twice found its way to the DYTP blog, inÌýÌýon a little-known Yiddish cultural society in Amsterdam, and a lively review,ÌýÌýwith fellow historian Rebecca Kobrin, of the Yiddish-language revival ofÌýFiddler on the Roof. The reflections shared in this post illustrate just a few of the ways that David enriched the academic fields he worked in and the countless lives he touched. May his memory be a blessing.